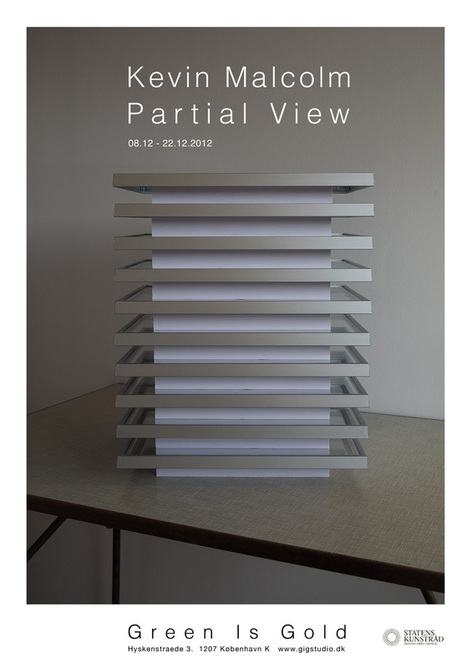

Partial View

New works by Kevin Malcolm (UK)

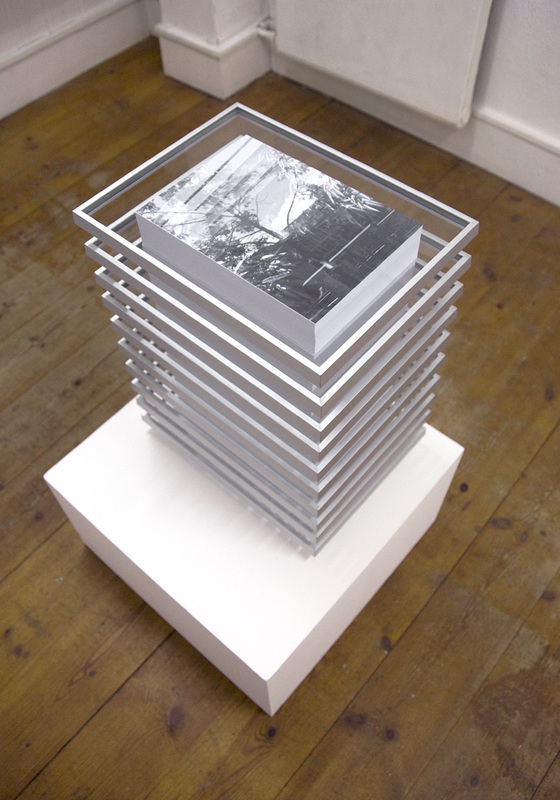

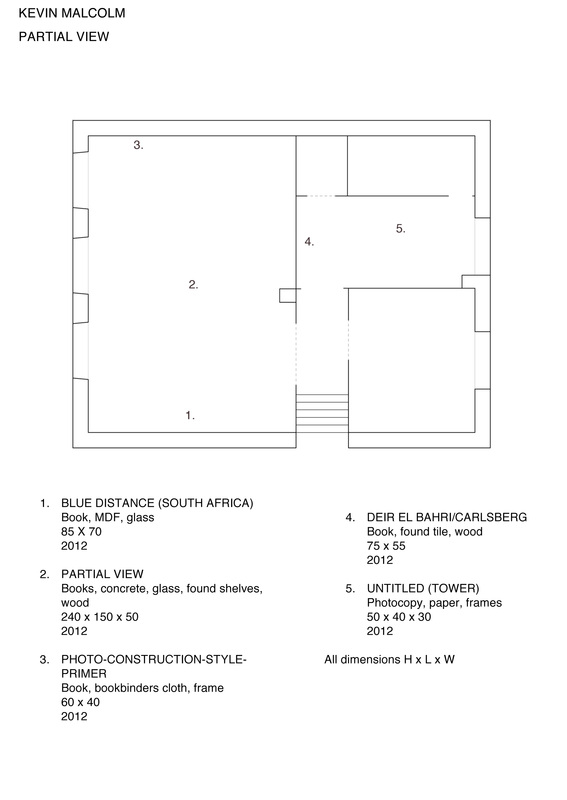

For Partial View Malcolm presents a new series of works which continue a dialogue between sculpture and photography. Investigating the role of the book as a storage unit of photographs these works highlight the tension between image and source. The mediative function of photography in the experience of architecture and place is questioned by way of mysterious assemblages imbued with associative potential.

"Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value. It is then that the hand retrieves this outer cast in dreams and, even as they are slipping away, makes contact with familiar contours."

- Walter Benjamin 'Dream Kitsch' 1925

Kevin Malcolm (b.1979) graduated from University of Glasgow in 2001 and The Glasgow School of Art in 2007. He is now based in Copenhagen.

www.kevinmalcolm.com

New works by Kevin Malcolm (UK)

For Partial View Malcolm presents a new series of works which continue a dialogue between sculpture and photography. Investigating the role of the book as a storage unit of photographs these works highlight the tension between image and source. The mediative function of photography in the experience of architecture and place is questioned by way of mysterious assemblages imbued with associative potential.

"Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value. It is then that the hand retrieves this outer cast in dreams and, even as they are slipping away, makes contact with familiar contours."

- Walter Benjamin 'Dream Kitsch' 1925

Kevin Malcolm (b.1979) graduated from University of Glasgow in 2001 and The Glasgow School of Art in 2007. He is now based in Copenhagen.

www.kevinmalcolm.com

The exhibition is kindly sponsored by the Danish Arts Council Committee for Visual Arts.

Press:

December 2012: Det skal du se! Kunstens.nu's redaktører Matthias Hvass Borello og Ole Bak Jakobsen anbefaler udstillingen Partial View.

December 2012: A conversation between Kevin Malcolm and Andreas Nilsson, on the occasion of Kevin Malcolm’s exhibition Partial View at GREEN IS GOLD. On Kopenhagen Magasin

December 2012: A conversation between Kevin Malcolm and Andreas Nilsson, on the occasion of Kevin Malcolm’s exhibition Partial View at GREEN IS GOLD. On Kopenhagen Magasin

Partial View

A conversation between Kevin Malcolm and Andreas Nilsson, on the occasion of Kevin Malcolm’s exhibition Partial View at GREEN IS GOLD, Copenhagen

AF ANDREAS NILSSON

In your recent publication Works Untitled, made in collaboration with Keith Allan and published by Green is Gold, there's a text by you I would like to quote from:

"Today I made some things. Some things made themselves.

Some were unsuccessful, others still wet and leaning.

Not work, not not work.

Just as pictures are at times only pictures, sculpture can just be sculptures. When a shelf is also a sculpture it displays it self displaying. What more, or less, could it do?

The thought (and production) process is accelerated in our current situation. Perhaps by dividing the weight of time we can slow it down. Half time."

What I really like about this passage is the way you describe the losing of control involved in the working process. And to me it seems that you really don't mind about losing control over your work. Is this correct and how would you describe this process?

Collaboration by its nature requires that you give up at least partial control of the process and the outcome. In my own practice I have a tendency to over-think things until they become stale, so collaboration is very useful in this respect. As the ideas and forms are more raw and untreated, blockages can often be bypassed, allowing the process to flow differently and the results to exceed expectations.

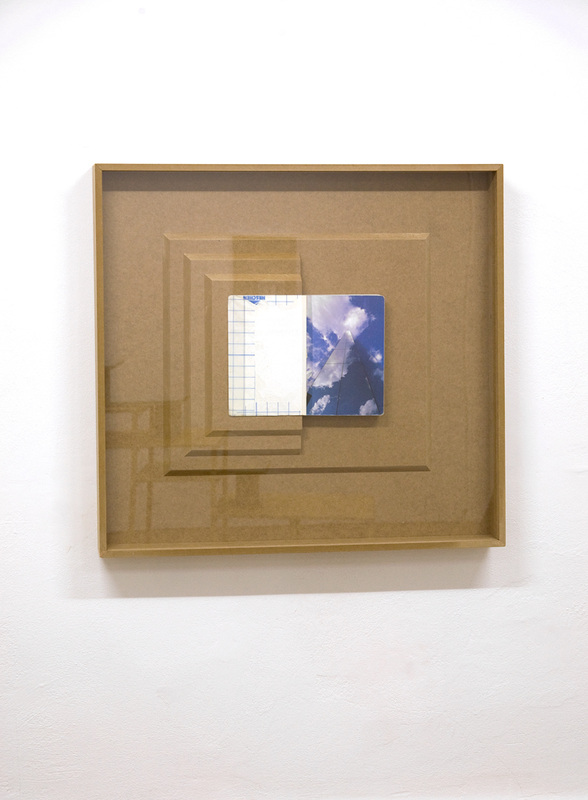

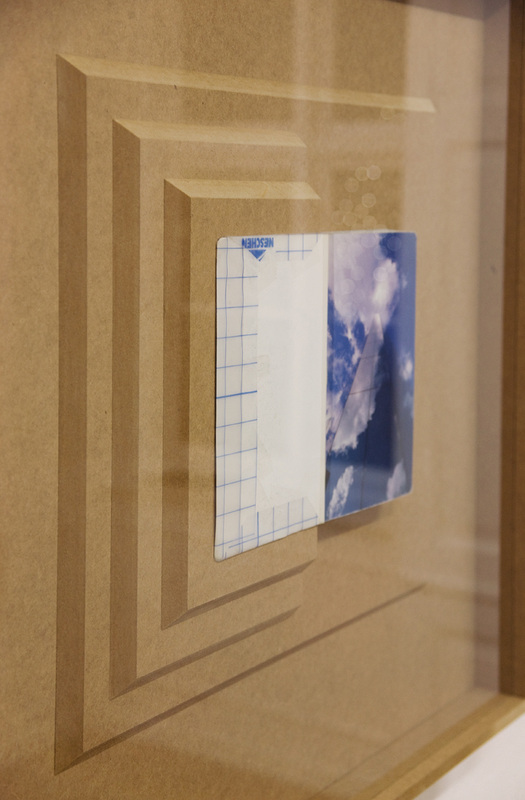

Using pre-existing elements, as I have done with the works in this exhibition, is also a way to lose control and cede a little autonomy. When working with material and cultural objects which have their own voice, a dialogue is opened and only develops further once the viewer is involved. If I present a book with a photograph of an ancient Egyptian burial temple alongside a tile from a demolished industrial building which until recently housed my studio, they start a conversation with each other and the viewer, but I can only, and would only, suggest what they might discuss.

To follow up on the books and the conversations they create, for your new work Partial Viewfor the exhibition at Green is Gold you have constructed a shelving system of wood holding small cylinders of concrete and books. The books, many of a historical nature, are placed both so you can view the content and some of which you can't. Can you say something about this, at the same time, revealing of and covering up of the history you are presenting?

I wanted to play with the meaning of the term 'open book' as someone or something that is easy to interpret and is without concealment. By placing objects or glass on them the books are held open at a particular page and so are at once both open and closed, the other pages are there but cannot be seen. Some images are prioritized while the others are hidden and can only be imagined, much like with history, hence the title Partial View. I'm interested in the potential of what may be on the other pages, the process of mentally filling up the rest of the book based on the suggestive possibilities of the photographic image.

Of course, the pages are of my choosing and reflect a combination of content which interests me and aesthetic decisions, like collage but where the motifs are not removed from their source before being presented. In this case, as in most of my work, I want to explore architecture and place and more specifically how they are experienced as image.

Where does this interest for architecture come from and what part does it play in your work? For example, in the new work Deir el Bahri/Carlsberg, an interior image is placed next to a covered image of what looks like a monumental building in a desert landscape. The method is somehow the same as in Partial View and an interest in architecture is clear, but also, to some extent, an interest in what becomes of the building - the ruin.

I think growing up in a city, and particularly in Glasgow where there is such a variety of spectacular buildings; gothic spires, Georgian terraces, canyons of sandstone tenements and a disproportionately large number of high-rise housing projects; led me to be interested in architecture from a young age. Exploring abandoned buildings and derelict sites, finding these out of the way places to go skateboarding and using concrete and discarded building materials to construct makeshift obstacles, shooting slides of these places and projecting them in nightclubs, were all a way of interacting with the city and with architecture, appropriating fragments of it to suit my needs or desires. Of course I was not really aware of this at the time, I just did it because it was fun and interesting. It wasn't until I studied at art school that I understood that these activities, and art, were a means to enter into discussion with architecture and on a very basic level enable a reduction of objective distance from the city, which is the environment in which the majority of people now live.

The ruin, and specifically the ruin in modernity has been a seam running through writing and art at least since the 19th Century, from Walter Benjamin, Robert Smithson, J.G. Ballard to contemporary artists like Jane and Louise Wilson or Cyprien Gaillard. With ruins the remains of a structure stand but the use is gone, they only function as something to be looked at and contemplated, or as a historical foundation for culture. I think the fact that they open this kind of poetic dream-space is what makes them so fascinating, especially for artists. I'm interested in which buildings are considered important, and why. Which structures enter the canon of memorable or remembered architecture, and what role photography plays in this. It is likely that the vast majority of buildings that are currently standing have been photographed. Either deliberately archived by those who commissioned or constructed them, or in holiday pictures, art books, Google street view, etc. Many of these photographs will outlive the buildings themselves, so for me there is something analogous then between a photograph and a ruin, they are not the same but they share similar properties in that they are both some kind of version.

This makes me think of what you have written on another occasion: "These images remind us that time is never frozen, least of all in photographs." This fits very well with the work your describing here and in the connection between a ruin and a photographed building - the aspect of time is always present. And it becomes even more apparent when I think of your working method which often includes found materials and objects. Leftovers (parts of ruins) become something new in your work and creates a kind of time warp.

To be a bit more concrete, can you give us some more overall thoughts on your exhibition at Green is Gold? What has been your starting point? For example, given your interest in architecture, how site-specific is your work?

I think the found materials, or leftovers you talk about were really the starting point for these works. I had found some shelves from a school with pencil marks on them and knew I wanted to build a sculpture incorporating them with books. I made replicas of the shelves so that I had enough to complete the structure I had in mind, so here you have the found object and the reconstruction side by side. This strategy of taking something and reworking it to suit a certain idea and again this return to the version. For the other works the books, or a particular image or spread, was the starting point and the work was built around that both as regards of form and materials. It is interesting to see what happens when these things from the recent past are thrust into the present, there are traces of the original function or meaning but now they become suggestive tools.

These found materials, objects or images also act as a trigger for the conception of works, whether they are present in the finished pieces or not. I suppose many artists work in this way, where you see something and an idea grows from it.

As to site-specificity, I tend to consider how to alter or approach the site (the exhibition space) to make it specific to the work rather than the other way round. This is a similar process to starting with an object and working outwards to provide some sort of space where it can speak, which I think goes back to this feeling of wanting to have a non-passive relationship with architecture and to the city as a whole.

Andreas Nilsson is curator at Moderna Museet Malmö. He is also co-founder of the independent art-association byrån.

A conversation between Kevin Malcolm and Andreas Nilsson, on the occasion of Kevin Malcolm’s exhibition Partial View at GREEN IS GOLD, Copenhagen

AF ANDREAS NILSSON

In your recent publication Works Untitled, made in collaboration with Keith Allan and published by Green is Gold, there's a text by you I would like to quote from:

"Today I made some things. Some things made themselves.

Some were unsuccessful, others still wet and leaning.

Not work, not not work.

Just as pictures are at times only pictures, sculpture can just be sculptures. When a shelf is also a sculpture it displays it self displaying. What more, or less, could it do?

The thought (and production) process is accelerated in our current situation. Perhaps by dividing the weight of time we can slow it down. Half time."

What I really like about this passage is the way you describe the losing of control involved in the working process. And to me it seems that you really don't mind about losing control over your work. Is this correct and how would you describe this process?

Collaboration by its nature requires that you give up at least partial control of the process and the outcome. In my own practice I have a tendency to over-think things until they become stale, so collaboration is very useful in this respect. As the ideas and forms are more raw and untreated, blockages can often be bypassed, allowing the process to flow differently and the results to exceed expectations.

Using pre-existing elements, as I have done with the works in this exhibition, is also a way to lose control and cede a little autonomy. When working with material and cultural objects which have their own voice, a dialogue is opened and only develops further once the viewer is involved. If I present a book with a photograph of an ancient Egyptian burial temple alongside a tile from a demolished industrial building which until recently housed my studio, they start a conversation with each other and the viewer, but I can only, and would only, suggest what they might discuss.

To follow up on the books and the conversations they create, for your new work Partial Viewfor the exhibition at Green is Gold you have constructed a shelving system of wood holding small cylinders of concrete and books. The books, many of a historical nature, are placed both so you can view the content and some of which you can't. Can you say something about this, at the same time, revealing of and covering up of the history you are presenting?

I wanted to play with the meaning of the term 'open book' as someone or something that is easy to interpret and is without concealment. By placing objects or glass on them the books are held open at a particular page and so are at once both open and closed, the other pages are there but cannot be seen. Some images are prioritized while the others are hidden and can only be imagined, much like with history, hence the title Partial View. I'm interested in the potential of what may be on the other pages, the process of mentally filling up the rest of the book based on the suggestive possibilities of the photographic image.

Of course, the pages are of my choosing and reflect a combination of content which interests me and aesthetic decisions, like collage but where the motifs are not removed from their source before being presented. In this case, as in most of my work, I want to explore architecture and place and more specifically how they are experienced as image.

Where does this interest for architecture come from and what part does it play in your work? For example, in the new work Deir el Bahri/Carlsberg, an interior image is placed next to a covered image of what looks like a monumental building in a desert landscape. The method is somehow the same as in Partial View and an interest in architecture is clear, but also, to some extent, an interest in what becomes of the building - the ruin.

I think growing up in a city, and particularly in Glasgow where there is such a variety of spectacular buildings; gothic spires, Georgian terraces, canyons of sandstone tenements and a disproportionately large number of high-rise housing projects; led me to be interested in architecture from a young age. Exploring abandoned buildings and derelict sites, finding these out of the way places to go skateboarding and using concrete and discarded building materials to construct makeshift obstacles, shooting slides of these places and projecting them in nightclubs, were all a way of interacting with the city and with architecture, appropriating fragments of it to suit my needs or desires. Of course I was not really aware of this at the time, I just did it because it was fun and interesting. It wasn't until I studied at art school that I understood that these activities, and art, were a means to enter into discussion with architecture and on a very basic level enable a reduction of objective distance from the city, which is the environment in which the majority of people now live.

The ruin, and specifically the ruin in modernity has been a seam running through writing and art at least since the 19th Century, from Walter Benjamin, Robert Smithson, J.G. Ballard to contemporary artists like Jane and Louise Wilson or Cyprien Gaillard. With ruins the remains of a structure stand but the use is gone, they only function as something to be looked at and contemplated, or as a historical foundation for culture. I think the fact that they open this kind of poetic dream-space is what makes them so fascinating, especially for artists. I'm interested in which buildings are considered important, and why. Which structures enter the canon of memorable or remembered architecture, and what role photography plays in this. It is likely that the vast majority of buildings that are currently standing have been photographed. Either deliberately archived by those who commissioned or constructed them, or in holiday pictures, art books, Google street view, etc. Many of these photographs will outlive the buildings themselves, so for me there is something analogous then between a photograph and a ruin, they are not the same but they share similar properties in that they are both some kind of version.

This makes me think of what you have written on another occasion: "These images remind us that time is never frozen, least of all in photographs." This fits very well with the work your describing here and in the connection between a ruin and a photographed building - the aspect of time is always present. And it becomes even more apparent when I think of your working method which often includes found materials and objects. Leftovers (parts of ruins) become something new in your work and creates a kind of time warp.

To be a bit more concrete, can you give us some more overall thoughts on your exhibition at Green is Gold? What has been your starting point? For example, given your interest in architecture, how site-specific is your work?

I think the found materials, or leftovers you talk about were really the starting point for these works. I had found some shelves from a school with pencil marks on them and knew I wanted to build a sculpture incorporating them with books. I made replicas of the shelves so that I had enough to complete the structure I had in mind, so here you have the found object and the reconstruction side by side. This strategy of taking something and reworking it to suit a certain idea and again this return to the version. For the other works the books, or a particular image or spread, was the starting point and the work was built around that both as regards of form and materials. It is interesting to see what happens when these things from the recent past are thrust into the present, there are traces of the original function or meaning but now they become suggestive tools.

These found materials, objects or images also act as a trigger for the conception of works, whether they are present in the finished pieces or not. I suppose many artists work in this way, where you see something and an idea grows from it.

As to site-specificity, I tend to consider how to alter or approach the site (the exhibition space) to make it specific to the work rather than the other way round. This is a similar process to starting with an object and working outwards to provide some sort of space where it can speak, which I think goes back to this feeling of wanting to have a non-passive relationship with architecture and to the city as a whole.

Andreas Nilsson is curator at Moderna Museet Malmö. He is also co-founder of the independent art-association byrån.

Photographer: Kevin Malcolm.